This major series of articles about the heroic rosh yeshiva HaRav Moshe Schneider whose talmidim, both Ashkenaz and Sephardic, went on to great achievements, was first published in 1994.

Part II

For Part I of this series click here.

For Part III of this series click here.

In the first part, we learned of HaRav Schneider's growth and early education, and how he wound up in the German city of Memel. He had a difficult time securing an appropriate shidduch, and it was the Chofetz Chaim himself who helped.

If in heaven they have a special department for those courageous Torah disseminators who established yeshivos in spiritually empty vicinities against mighty odds, Rav Schneider will have an eminent place there.

And if there is a special department for the brave-souled who cried out, "Give me Yavne and her wise men!" at a time of bitter destruction — Rav Schneider will have a distinguished spot there.

And if there is a special department for those who revived Torah study at a time when it was almost lost and forgotten—Rav Schneider will be in the front row there too.

Rav Schneider was truly among the main disseminators of Torah in the last century. An unusual and dynamic individual who transplanted Torah and made it flourish in spiritual wastelands where no one believed it was possible, he did the painstaking groundwork that enabled the barren atmosphere in England and France to give way to the dozens of yeshivos, religious institutions and frum communities that are in existence today.

Part 2

Starting a Yeshiva in Memel

After the wedding, the young couple stole across the border and returned to Memel. Rav Schneider promptly founded his yeshiva, which in time acquired a name as a full-fledged Litvishe yeshiva. Boys from Russia began to stream across the border to attend. Even from Memel itself, some came because they had seen the announcement that a yeshiva was opening up and it was accepting young students without tuition. Some boys even left their places of work to come attend the yeshiva.

Rav Schneider's approach bordered on the abandon, otherworldliness and inexhaustible bitochon of Novorhodok. He had long ago given up all materialistic aspirations for himself and he offered his talmidim to share the same life with him.

Throughout the many decades that his yeshiva existed and the many gilgulim it went through, those who were intimately connected with the yeshiva knew it ran on high-octave fuel —the high octaves of tefillah in which he cried out to the Ribono shel Olam. There was no regular income, no big supporters nor other normal causes to which one could ascribe the yeshiva's existence.

The yeshiva in Memel barely subsisted, but for most of the bochurim, who had lived on a similar standard in their homes in Lithuania, this was unexceptional. They had come to the yeshiva to imbibe spiritual food, and they found themselves indeed at a feast.

It made no difference that the dormitory had to double as the dining room. The "beds"—wooden frames covered by a filled sack which were placed on the benches—were moved out of the way at mealtimes. At night, the beds were returned to their places.

At first, Rav Schneider decided to support his yeshiva by selling seforim and investing the profits in the yeshiva's upkeep. However, he quickly found his business endeavors doing too well, and was afraid that the business world would prove too engaging and enticing. He closed up his business and decided that the Jewish community would become his partner in the yeshiva's existence.

The yeshiva was visited by many money crises, but Rav Schneider's surging bitochon in Hashem managed to buoy the yeshiva each time. His daughter would later recall that from her earliest youth, the family was "accustomed" to miracles. The bank account would register a deficit, there wasn't another potato to feed the bochurim... and then a donation would suddenly arrive. This happened again and again with the yeshiva.

One of Rav Schneider's unusual policies was not to charge tuition from his students' families—even from those who could pay. "If you charge tuition," he said shrewdly, "the parents will feel that they are "yachsonim" ("privileged") and then they'll come and dictate how to run the yeshiva and handle their children."

He assiduously refused any offers to establish a steering committee for the yeshiva. He was wary of gaining for himself baalebatim who would begin dictating how to run the yeshiva and whom to accept. That this policy would insure constant financial crises did not move him.

Until World War I, when the yeshiva disbanded because of the war conditions, Rav Schneider and his talmidim did not have valid entry permits to Germany. Police visited the yeshiva several times, and each time the yeshiva survived their scrutiny intact. Once, the police entered and then walked out without saying a word—a clear miracle. Another time, the police agreed to take bribes and accept Rav Schneider's supplications—another blatant miracle, considering the German mentality.

Rav Hirsch Levinson

The uproar that the yeshiva's founding in Memel caused did not affect its growth and good name. Rav Hirsch Levinson, the Chofetz Chaim's son-in-law, came to visit the yeshiva and was amazed. "This is truly a rose among the thorns! Perhaps in Lithuania or Poland this yeshiva would not be exceptional, but that such a yeshiva could exist in Germany! Who would believe it!"

Rav Of The P.O.W. Camp

When World War I broke out, and Germany and Russia became enemies, Rav Schneider was placed in detention with other Russian citizens. After deciding that he was not dangerous, the Germans sent him to a small village on the coast, which contained hundreds of other Russians, most of whom were Jews. The plan was to send all the Jews back to Russia through Scandinavia, but this scheme never materialized.

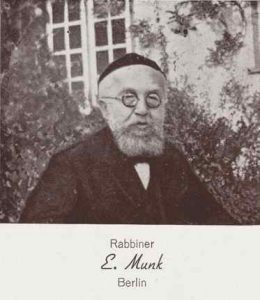

HaRav Ezra Munk zt"l

In the meantime, the detainees were unorganized and disoriented. Where others saw misery and hopelessness, Rav Schneider saw the potential for a fine temporary Jewish community. Contacting Rav Ezra Munk, one of the rabbonim in Berlin and a liaison with the German government, Rav Schneider received permission to travel to Berlin. He was provided with documentation from the village mayor giving him the authority to found a Jewish community and to provide all required services.

He returned with a shochet's knife, seforim, a shofar, and all the other necessities of Jewish life and quickly organized provisions for all the Jews. A kosher shechita and kitchen were set up, and shiurim organized in which most of the men participated.

The Yomim Noraim were spirited and electric in this makeshift community. For Sukkos, Rav Schneider received permission to build sukkahs. The holiday passed in good spirits, with the non-Jews watching the detained Jews dancing and singing.

The good times didn't last long. A new order sent the Jewish detainees to a POW camp in the village of Holtzminden in the district of Westphalia, deep in the interior of Germany. In this POW camp, the Jews were treated brutally, and forced to do hard labor.

Rav Schneider was able to secure certain benefits for them, particularly of the kind that would help them minimize Shabbos transgression. Besides Rav Schneider, who was already considered the rav of the group, everyone had to do hard labor.

After some time Rav Schneider was allowed to exit the camp and have free passage in the city as long as he reported daily to the police station. When he heard that all government workers could apply for the same free passage status that he had received, he convinced a few German craftsmen to accept Jewish artisans from the POW camp to their place of work. Through his influence, most of the Jewish men received work, and were freed from the camp. Many of these men settled in the city, and their wives and families were allowed to join them.

Tallis Production And Mikveh Construction

However, family life was seriously jeopardized because there was no mikveh. Once again Rav Schneider wrote to Rav Munk in Berlin, and received from him the necessary architectural plans in German. He rented two rooms in a building, received the necessary permits, hired a contractor and erected a mikveh. At the end of the project, he sent the bill to Berlin, and a worthy Jew undertook to pay the cost.

It was impossible to buy tzitzis during the war since the German government had appropriated all the wool and linen for its own use. Again, with Rav Munk's help, Rav Schneider received a permit to buy a liter of linen. He went out to several farmers who grew linen, and when he saw that they didn't take the permit from him, he used it to purchase several liters of linen.

After an exhausting investigation, he found an old non-Jewess who was expert in weaving threads by hand, and with her help was able to produce the tzitzis strands. After additional efforts he acquired several rolls of cotton, and began to produce thousands of talleisim.

He wrote to different prison camps, "Do you need talleisim? How many?"

The prompt answer was "Yes! But we cannot say how many."

So he sent them packages of tzitzis, according to his guess of how many were needed. When he received warm letters of thanks and requests for more, he continued sending until none were left. The bill for this enterprise was also sent to Berlin.

In 1917, Rav Schneider received permission from the German government to leave this village and to settle wherever he wanted. His yeshiva in Memel had long ago disbanded and nothing was left of it. He promptly went to Frankfurt and began a business.

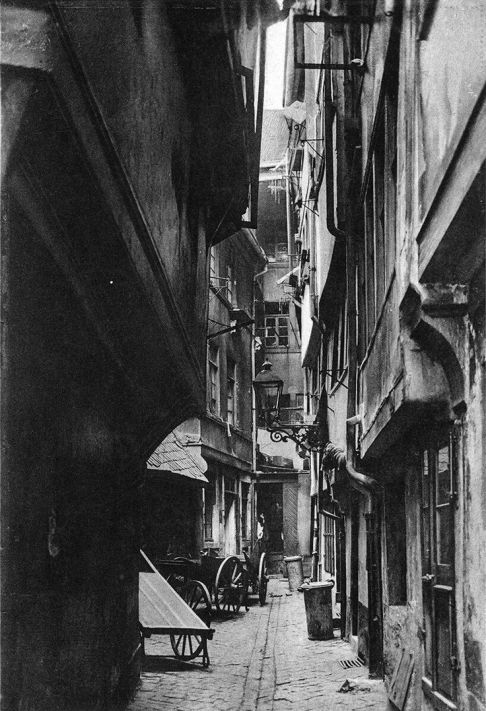

Frankfurt end of 19th century

A Litvishe Yeshiva In Frankfurt

This was another one in a series of moves he did that was not only striking a stake in new territory, but was striking a stake in a seemingly hopeless desert land. A Novardok-style yeshiva may have been appropriate in impoverished Poland and Russia — but in Germany? It was true that there was a strong Orthodox Jewish kehilla in Frankfurt led by HaRav Samson Rafael Hirsch's able son-in-law, Rav Breuer, but the intensive abandon to Torah study known in Poland and Lithuania was unknown.

Moreover, this lifestyle appeared to many to be incompatible with basic German values, including decorum, respectability, interaction with the outside world, and of course, Torah im derech Eretz. In addition, German Jews often looked down at the "Ostjuden" and were suspicious of anything that had to do with Eastern Europe.

HaRav Schneider's keen spiritual eye soon noticed that the city was full of East European Jews who had been taken prisoner at the war front. Their children were wandering around the streets, with no one to teach them Torah. Rav Schneider stood up in public and gave fiery speeches in shuls, until he succeeded in founding a Talmud Torah in which hundreds of children eventually learned, and a Tiferes Bochurim, an evening framework for Torah study, for those bochurim who had to work during the day.

As the refugees from East Europe continued to pour in, Rav Schneider had the impetus to found another yeshiva. When skirmishes over the borders increased between Poland and Russia at the end of the war, many bochurim escaped to Germany, and, to their surprise, they found a full-blooded Litvish yeshiva established in Frankfurt where they could continue their Torah study.

Yeshivas Toras Emes grew continually until it had over 100 bochurim. Some of them reached semichoh certification.

How did the yeshiva receive its support? The Germans looked with suspicion at the flood of East European immigrants coming to their land, and many of the German Jews also felt distaste for their "uncultured" brothers. Once again, Rav Schneider had put himself into an untenable position. "It's impossible to keep a yeshiva here," was the unremitting advice he heard from many well-meaning friends throughout the 20 years he had his yeshiva in Frankfurt.

Nevertheless, the special hashgacha protis that surrounded him in Memel came to his aid here too. Although his yeshiva was never free of debt and it suffered want continually, it remained a proud fixture on the Jewish map of Frankfurt until Rav Schneider was forced to flee to England.

Seventy years later Rav Schneider's grandson was at the airport in Lod seeing his mother off from Israel. Afterward he approached a heimishe Jew and offered him a ride to Jerusalem. On the way the passenger discovered that he was riding with a grandson of Rav Schneider.

"We have a story in our family about my grandfather and Rav Schneider," the Yid suddenly spoke up. "My grandfather was a well-to-do German businessman, who was becoming more and more committed to Judaism. He had started a chavrusa in Chumash with the rav in his small town, and they arrived at the passage in Shema "You shall love Hashem... with all your possessions." The rav explained that this means that one should demonstrate his love for Hashem by means of giving his possessions.

"My grandfather's soul was set on fire, and he declared that he wanted to give away all his possessions to a worthy cause, to show his love of Hashem.

"`But to what worthy institution should I give the money?' he asked.

"The rav answered, `There is a yeshiva in Frankfurt run by a Rav Schneider. This yeshiva badly needs support. It is a very worthy yeshiva, a fitting place to put your money.'

"So my grandfather sold all his possessions, and sent the money to Rav Schneider's bank account."

"That was your grandfather!" Rav Schneider's grandson replied in amazement. "I indeed heard that once the bank phoned my grandfather and notified him that a large sum was waiting for him in the bank. He then found out that an anonymous, fine Jew had suddenly decided to send this large sum to the yeshiva. But never did I imagine I would actually meet a grandson of the man who had done it!"

Winning the Support of Local Residents

A few local Frankfurt Jews became his dedicated supporters. One, a Mr. Z. Salomon, was a butcher. Not only did he supply the yeshiva with meat and money, but he also devotedly helped to collect funds.

Mr. Emanuel Kaufman, a reputable businessman, volunteered to go with Rav Schneider to the homes of wealthy Jews to make sure they received him with the proper respect. The journalist Rav Zelig Shachnowitz, the editor of the Israelit, who had been one of the first teachers in Rav Schneider's Talmud Torah, helped him with the authorities where necessary.

There was a need to hire a rosh yeshiva to do most of the teaching, since Rav Schneider spent much of his time on the road to cover the yeshiva's huge expenses. He found the right person in Rav Moshe Karpel, a sharp boki and talmid chochom of stature, who had come to Frankfurt in 1920, a refugee from Lithuanian Poland. He was rosh yeshiva in the yeshiva for over 10 years.

Rav Schneider had regular places throughout Germany that he would visit every year. He came not only to collect money for the yeshiva, but also to see to it that the fledgling communities of East European Jews were having their needs provided for.

During the 20's he helped establish mikvehs and Talmud Torahs for the children. He was influential in arranging rabbinical posts for Rav Yom Tov Lipman Rakov in Wakersheim (he later became a rosh yeshiva in his yeshiva in Frankfurt) and Rav Ragoznitzki in Heidelberg and Leipzig (he ended his life as rav in Cardiff, England).

He was instrumental in bringing melamdim from Poland to teach in the chadorim. One of these, Rav Benzion Berman, eventually went on to teach in the yeshiva too.

This "rose among the thorns" acquired for itself a name as a yeshiva of the same standard as the famous yeshivos of Poland and Lithuania. It was visited by gedolim such as Reb Leib Vilkomirer; HaRav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky; HaRav Moshe Mordechai Epstein of Slobodke; the Czortkover Rebbe; Reb Shmuel Yitzchok Hillman; and HaRav Yosef Cahaneman, the Ponovezher rav, who consented to give a shiur to the bochurim.

HaRav Moshe Mordechai was confronted with such sharp questions from the bochurim to his shiur, that he recited "Shehechiyanu" that such a yeshiva could exist in Germany!

The yeshiva had a tremendous impact on the wider Jewish community in Frankfurt. It generated a strong kinas sofrim that spurred the Orthodox community founded by HaRav Hirsch to establish a serious yeshiva program, as well as the Orthodox community which belonged to the general Jewish establishment. When the rabbinical leaders saw the success which Rav Schneider garnered they drew a kal vochomer to themselves, "If this impoverished foreigner could found a yeshiva and be so successful, how much more so are the local Jews required to found and support a yeshiva!"

Although Rav Schneider was very different from the typical German Jew, he was respected by all for his deep yiras Shomayim and devotion to Torah.

End of Part 2